“Among the wise I am the only one that goes in for hobbit-lore: an obscure branch of knowledge, but full of surprises.”

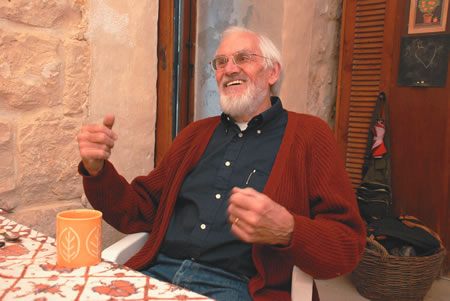

So said another famous white-bearded luminary about another small and closely-knit provincial community, albeit in a purely fictitious world. As he approaches his 80th birthday, Professor Jeremy Boissevain is likely to sympathise with Gandalf the Grey’s take on the halflings of the Shire: after all, he too admits to being constantly surprised by the society he has observed, dissected and commented upon for well over 40 years.

Boissevain first came to Malta in September 1961, and wrote his doctoral thesis – later published as “Saints and Fireworks – Religion and Politics in Rural Malta” – in the summer of 1962. Since then he has written dozens of academic papers on the subject of Malta, the Maltese and Malteseness in general; many of which are now in the process of being edited into a single volume, due for publication shortly.

Perhaps a little foolishly, the first question I ask concerns how much has actually changed since he first came to Malta as a London School of Economics scholar.

“Quite a lot, I would say,” Boissevain muses some 45 years later in the kitchen of his Naxxar home. “Malta was going through difficult times. Today there isn’t the tension there used to be back then. Most of the issues have since died down.”

In truth, the Malta of “Saints and Fireworks” was very much a nation in transit, halfway between occupation and independence. The Constitution was still in limbo after the unrest of April 1958; Malta had reverted uneasily to Colonial rule, and Opposition leader Dom Mintoff was still labouring under an excommunication edict after Archbishop Michael Gonzi’s notorious Lenten pastoral of 1961.

These were in fact the great formative years, characterised by uncertainty, social and political upheaval, and an ill-concealed national obsession with controlling, curtailing and suppressing any form of dissidence or subversion, whatever form it took.

Interestingly enough, a comment given by Boissevain to another interviewer – Alan MacFarland in 1983 – indicates the sort of tensions he refers to: “When I arrived I called on the new Lieutenant Governor and he was sitting uneasily. He said: ‘Look here, if I have any evidence of you contacting the unions or the Labour Party, you will be on the next boat out of here…’”

But for all the major tectonic changes of the intervening decades – independence, the end of British naval presence, 16 years of Socialism, 1987 and all that – what seems to impress Boissevain the most are the little things. For instance, the fact that people nowadays tend to sign the letters they write to the newspapers.

“One thing I’ve noticed is that people are no longer afraid to openly criticise the government,” he says indicating a pile of newspapers on the kitchen table. “Not that there wasn’t always lots of grumbling in the past. There was. But back then, criticism was rarely expressed in public, and when it was it would always take the form of anonymous letters to the papers.”

Today, by way of contrast, attaching one’s name to one’s public gripe about the issue of the moment seems to be par for the course. Boissevain lists a number of factors that contributed to this newfound sense of social and cultural emancipation. Foremost among them, the simple observation that the political changes after 1987 gave people more freedom to express their views.

“Under Labour in the 1970s and 1980s there was real fear of recrimination. One image that stuck with me from those days was how people would look over their shoulder to see if anyone was listening.”

But while Boissevain describes these changes as the inevitable consequence of the fall of the ancienne regime, certain other corresponding changes that he expected as a consequence have spectacularly failed to materialise.

“I have made many predictions, and many of them have been proved wrong,” he admits, exhibiting all the intellectual honesty for which is admired throughout the academic world. One of his misfired predictions concerned the same system of patronage networks that he had famously explored in “Saints and Fireworks.”

“I thought that patronage would decline over the years. In fact I had written an article about this; it was called ‘When the saints go marching out’…”

Boissevain himself attributes this error of judgement to youthful exuberance. “I suppose it’s the hubris of the young, inexperienced person – in my case, an anthropologist – who took too short a view of history,” he admits. “My predictions were based on short-term observations over a single year. In such a short time-frame you can’t get a real historical perspective. And besides, in the 1960s anthropologists were encouraged not to study history. Traditionally we worked on cultures without written archives…”

With hindsight, it is easy to see why it seemed such a likelihood at the time. “It was in the middle of the 1970s when I wrote that article,” Boissevain recalls. “Mintoff had just been re-elected, and all the ‘bazuzli’ were going to be eliminated. One by one, all the old traditional patrons – the professional classes, the church – either had or were about to have their wings clipped by the Labour government. There was a sense of change in the air…”

But while change undeniably came, the expected decline in patronage proved elusive in the long run. In fact, Boissevain admits being surprised at the fact that it appears to have grown stronger ever since.

“In the end the saints didn’t go marching out at all,” he concludes with a wry smile. “Ministers have become the new saints. Over time they have accumulated enormous power, and an almost cult-like status. There is also the old Maltese attitude, whereby people vote the way they do partly for ideological reasons, but also because they would know well-placed people who can intercede on their behalf. Here, anyone can communicate directly with real power…”

Another of Boissevain’s predictions to go slightly awry concerned the village festa itself: the same festa which originally put him on the world anthropological map.

Again, there were many reasons back in the 1960s to think that the tradition would slowly peter out and vanish. “The social changes taking place in village cores, with outsiders moving in and locals moving out, meant that fewer and fewer people would identify themselves as ‘from the village’,” he points out. “The villages themselves were growing and changing. There was also mass emigration at the time… at every point, all these changes seemed to translate into a situation whereby boys were being taken away from the village, and from organisation of the festa, never to be replaced...”

From this vantage point, a gradual extinction seemed more or less inevitable. But despite this mass exodus of young male volunteers, Maltese festi have not only stubbornly refused to keel over and die, but they have simply carried on growing and growing, until even Jeremy Boissevain himself is disconcerted by their garish enormity.

“Today, the village feasts lasts for a whole week, instead of the traditional three days. The fireworks are noisier, the band club rivalries are more intense…”

But while some of his earlier predictions for Malta may have not come to fruition, on other issues Boissevain has been chillingly vindicated. For instance, he once cited Malta as a typical example of the deleterious effects of mass-tourism on the environment.

“In short, the NTOM (today’s MTA) has increasingly commoditised Malta's culture and physical environment without paying much attention to the impact of this commercialization on its citizens,” he concluded in a paper on the subject published in 1996.

This commoditisation can in fact be taken almost as a hallmark of the way things have gone in a wide variety of spheres. Boissevain is constantly appalled at the way we have allowed commercial interests to annex vast swathes of our countryside, giving little or nothing in return.

“Today, it is no longer the local council that welcomes you when you drive into a town. It is HSBC, or some other business interest. It seems that sponsorship is recognised as a justification for almost anything.”

To illustrate his point, Boissevain invites me to consider the sheer proliferation of commercial billboards which shut out the view of the countryside wherever you are.

“This doesn’t happen in other parts of Europe. It doesn’t happen in the Netherlands, which is a terribly commercially-minded country. I have just driven through Sicily, and you don’t see them there either. In Malta, on the other hand, you are assailed by billboards wherever you look. At every point, the beautiful countryside is shut out from view...”

Boissevain seems to suggest that the “right to make money” is something of a universally acknowledged value in Malta, and is used to justify things which would be deemed unacceptable elsewhere. Paradoxically, however, he also recognises that the same commercialisation that has claimed as its own so much of our natural landscape, has also galvanised civil society to voice its opposition in a way that politics never succeeded in doing.

Malta has experienced the emergence of an environmentalist counter-culture which resides outside the sphere of mainstream politics. “Today, there is pressure on government to consult which didn’t exist before. Look at the recent cases of the Xaghra l-Hamra golf course, the proposed landfills at Mnajdra, and the Ramla l-Hamra decision. These would not have happened if government was still insensitive to popular criticism.”

Much of this pressure can be attributed directly to a reaction against the annexation of Malta by tourism-related interests.

“There were some notable defeats in the beginning”, Boissevain acknowledges. “The Hilton, for instance, or the tuna farms issue. But since then the number of projects to be stymied on account of popular pressure has steadily grown.”

But there is another side to this equation. Jeremy Boissevain also points out that the reaction against this consumerist appraisal of things has to date been limited to the middle classes, suggesting that environmentalism is likely to remain an elitist affair for some years to come. As an example, Boissevain cites changing trends in the property market.

“Old houses are valued now, but this is a relatively recent development. In the 1980s there was the prevailing view that ‘new’ was an intrinsic value in its own right. In some respects this has survived, but there is today some appreciation for traditional town houses, antique furniture, etc.”

The catalyst for change took the form of foreigners who started showing an interest in typical Maltese properties, and were ready to pay for them accordingly. One effect of this was that the transition moved from the foreigner to the local middle classes, largely overlooking the grassroots in the process.

“Foreign interest bled over into the local bourgeoisie. Couples started buying and converting houses in the old village cores; suddenly old houses were themselves a commodity,” Boissevain observes, citing his own Naxxar home as a prime example.

But for the same reasons, concern with the preservation of heritage (although Boissevain dislikes the word, preferring “an interest in the vernacular” instead) has similarly been limited to the bourgeoisie: a view which is strongly reinforced by even a cursory glance at the who’s who in today’s burgeoning environmental NGO scene.

This view is also reinforced that while environmental concerns have been pushed up the political agenda of late, they have failed to dent the hegemony of the traditional power structures.

“I had hoped the Green Party would garner enough votes to create the necessary leverage to protect Malta from the inroads of developers,” he says, “But when push came to shove, they never got the necessary percentage to make that difference. People still tend to vote in blocks, even if they are more critical of the traditional parties.”

But Professor Boissevain does acknowledge what appears to be a sea-change in Malta’s attitude towards politics and the environment. “The major shift seems to be that activists in various NGOs are training a new set of activists in politics,” he says. Perhaps understandably, however, he is unwilling to make any predictions as to how this ‘new way of doing politics” will pan out in future.