Karl Schembri - Tripoli

Upon touching Libyan ground last Wednesday, President Eddie Fenech Adami and his entourage quickly realised that the official programme was scrapped even before the private jet landed.

The much-expected meeting with Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi was scheduled late in the afternoon, but the black executive cars with the slight sprinkle of desert sand running on the side waiting for the Maltese delegation at Tripoli airport were immediately rushing at 100 miles an hour, shortly after a motley brass band struck up a merry cacophony bearing some resemblance to l-Innu Malti.

They were heading, it soon transpired, towards the Bab al Aziziya compound, the so-called “site of the futile American aggression”.

It is the same site where, on the night of 15 April 1986, American fighter planes that had left from British bases, precision-bombed Gaddafi’s own residence in the dead of night, upon direct orders from US President Ronald Reagan.

On that fateful night, then Maltese Prime Minister Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici phoned Gaddafi informing him that unauthorised planes were flying over Maltese air space, heading south towards Tripoli.

The Colonel was saved in the nick of time. The bombs were dropped just as he and his family were rushing out of the house, destroying the area and killing civilians, including Gaddafi’s adopted daughter.

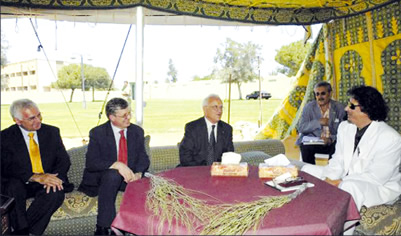

No wonder, then, that more than two decades later, Gaddafi enquired with Fenech Adami about the health of Dom Mintoff and Mifsud Bonnici in this week's meeting under the air-conditioned Bedouin tent – the latter being his veritable saviour for whom red carpet treatment is reserved whenever he goes to the Jamahiriya.

“How is Mintoff?” Gaddafi asked the President, moving on to inquire about Karmenu Mifsud Bonnici’s health, after the journalists were ushered out on the impeccable turf inside the Bab al Aziziya compound that is now home to a bunch of camels and a limping horse.

The question harks back to the time when Malta and Libya were truly close friends as the US-dominated western world was branding our southern neighbour as a pariah state.

Since then, both countries have changed beyond recognition. Most notably, Malta is in the EU – somehow closing its open doors to Libyans, who since 2004 require visas to enter – and Libya has been brought back to the international fold since its leader denounced weapons of mass destruction in the same year, with the ensuing lifting of UN sanctions.

It was in the same year of Malta’s entry into the EU, when Prime Minister Lawrence Gonzi was unceremoniously snubbed by Gaddafi, letting him wait for three whole days before summoning him just as he was boarding the plane back to Malta.

In contrast, four years later, the President is rushed to the customary tent greeting high dignitaries in what turned out to be a lengthy chat and lunch with the Libyan leader wearing a cool, impeccably white suit with a massive outline of Africa as lapel. Fenech Adami came out beaming, together with foreign minister Tonio Borg and social policy minister John Dalli.

The latter is possibly part of the answer to the Colonel’s change of heart towards good old Malta hanina. Dalli – who has extensive business interests and consultancies in the Jamahiriya – makes it clear he hates any hint of bad press about his Libyan partners, even when it is about the historical timeline outlining the regime’s spectacular rehabilitation.

He is not amused, for example, when the free press points at Reagan’s highly insulting adjectives to the Colonel, to point at the impressive turnaround in US-Libya relations.

“You keep writing the same old stupidities,” he told me.

To him, it is just useless chatter that will only undermine Malta’s efforts to keep good business relations with Libya.

And yet, it is Gaddafi himself who referred to his long-standing enemy as “the loony Reagan” in a speech he gave last June, stirring up the rhetoric and propaganda of old that has seen his regime in some of the toughest moments at the height of tensions with the US.

“Those who want to learn democracy should come to the Libyan school and learn from it and begin to learn the alphabet of democracy; we will teach them the direct popular democracy,” he said, lambasting America as a veritable dictatorship.

Indeed, contradictions in Libya just stare you in the face, starting off from the Corinthia Bab Africa Hotel. The gem of Maltese investment and design belonging to the Corinthia group that was boycotted by the US during the years of the embargo had four full floors serving as the American embassy until recently.

A gigantic hand of steel crushing a US fighter plane stands still at the Bab al Aziziya compound just in front of the bombed residence, dubbed “Steadfast House” and left as a standing memory of the air raid.

The famous Green Book penned by Gaddafi mixing tenets of socialism, Islam, and Arab and African nationalism, still gets its fair share of publicity in Tripoli, which still hosts the Centre for Green Book Studies and produces professors of Jamahiri Thought despite all the evidence that this political manifesto has long been shelved for good.

Gaddafi, once paymaster and arms dealer to a host of terrorist (or resistance – depending on which side you’re on) groups, is now on first-name terms with Tony Blair and George Bush.

Giant multinationals are now entering Libya, which has visions of becoming the new Dubai, although the service industry remains totally lacking. Yet even Maltese investment – relatively modest compared to the billions of dollars seeping slowly onto Libyan soil – has had its long-term vision proven as the Corinthia Bab Africa remains the number one reference point for all the business and diplomatic pilgrims to the Jamahiriya.

Another Maltese project under construction a few kilometres away from the centre, also by the Corinthia group, is the exclusive Palm City estate overlooking the coast, which is also bound to be a huge success when it is ready next year – meant to coincide with the 40th anniversary since the Al Fatah revolution.

Offering over 400 luxury bungalows, villas and apartments for long rent starting from €2,000 a month, it will be the lavish refuge for foreign executives working here.

Yet the unpredictable nature of the reformed despot remains untouched. As the Maltese delegation was touring the outstanding prehistoric artefacts and extraordinary Greek and Roman statues in the Tripoli museum, which is housed in the castle built by the Knights of St John in Green Square, police stood outside the Swiss Embassy “for security reasons” and the Nestlé offices remained closed as the Hannibal Gaddafi incident in Switzerland somehow remains a burning issue.

And later on the same day, Libya announced it was negotiating with Moscow to buy Russian weapons and for the construction of a nuclear power station, besides the confirmation that Tripoli had a “special relationship” with Russian gas giant Gazprom to develop new projects in Libya.

But even with Malta things are seemingly turning for the better. Fenech Adami, who visited Gaddafi again before coming back to Malta, described his meeting with the Colonel as “long and very cordial” in which both did a “full review of the bilateral relations between the two countries”.

What was of essence, however, was the willingness to solve the long-standing dispute of oil exploration, the more recent fishing zone controversy, irregular immigration and a new double taxation agreement.

“My assessment is that there is a strong political will to seal agreements in the coming weeks,” the President said, hinting at a possible breakthrough in Gonzi’s next visit expected later this month.

Dalli, who is burdened with solving unbearable waiting lists at Mater Dei, signed an agreement with his health counterpart to share knowledge about diseases, particularly diabetes affecting the two Mediterranean countries.

Among the issues that remained untouched, despite Tonio Borg’s presence, was Libya’s plans to have nuclear energy plants thanks to France’s (and now Russia’s) generous offer just as three of its own reactors are leaking radioactive material.

“We didn’t think it was a question to go into at this point in time,” Fenech Adami replied when asked whether the subject was raised at all.

Which is just as well – given the Libyan leader’s generous hospitality, one might as well not cross him with petty questions which the Maltese government itself considers to be a “non-issue”. In John Dalli’s own words, we might as well not “shoot ourselves in the foot”.